Port Operations

Port operations represent the critical interface between land and sea transport. A modern container terminal is a highly orchestrated environment where vessels berth, containers are discharged or loaded by massive cranes, thousands of boxes are stacked and tracked in the yard, and trucks cycle through gates on tight schedules. Efficient port operations directly determine vessel turnaround time, transit reliability, and ultimately the cost of ocean freight.

Understanding how ports function helps freight forwarders plan realistic transit times, helps shippers avoid storage charges, and helps logistics professionals troubleshoot delays when containers are stuck at terminal.

Port Roles and Stakeholders

A container terminal involves the coordinated efforts of multiple parties, each with distinct responsibilities:

| Stakeholder | Role |

|---|---|

| Port Authority | Owns or governs the port infrastructure, grants concessions to terminal operators, regulates safety and environmental standards |

| Terminal Operator | Manages day-to-day operations — berth scheduling, crane allocation, yard planning, gate control. Major operators include PSA, Hutchison, DP World, and APM Terminals |

| Shipping Line (Carrier) | Operates vessels, books berth windows, provides stowage plans, and owns or leases the containers |

| Customs Authority | Inspects cargo, clears imports/exports, enforces trade regulations. In the U.S., this is Customs and Border Protection (CBP) |

| Freight Forwarder | Coordinates cargo movement on behalf of shippers, handles documentation, arranges trucking to/from the terminal |

| Trucking Company (Drayage) | Delivers export containers to the terminal and picks up import containers after release |

| Container Freight Station (CFS) | Handles consolidation and deconsolidation of Less than Container Load (LCL) shipments near the terminal |

| Surveyors & Inspectors | Verify cargo condition, container integrity, and compliance with safety regulations (e.g., dangerous goods inspections) |

The distinction between port authority and terminal operator is important. The port authority is typically a government or quasi-government entity that manages the overall port, while terminal operators are private companies that lease individual terminals and run the equipment.

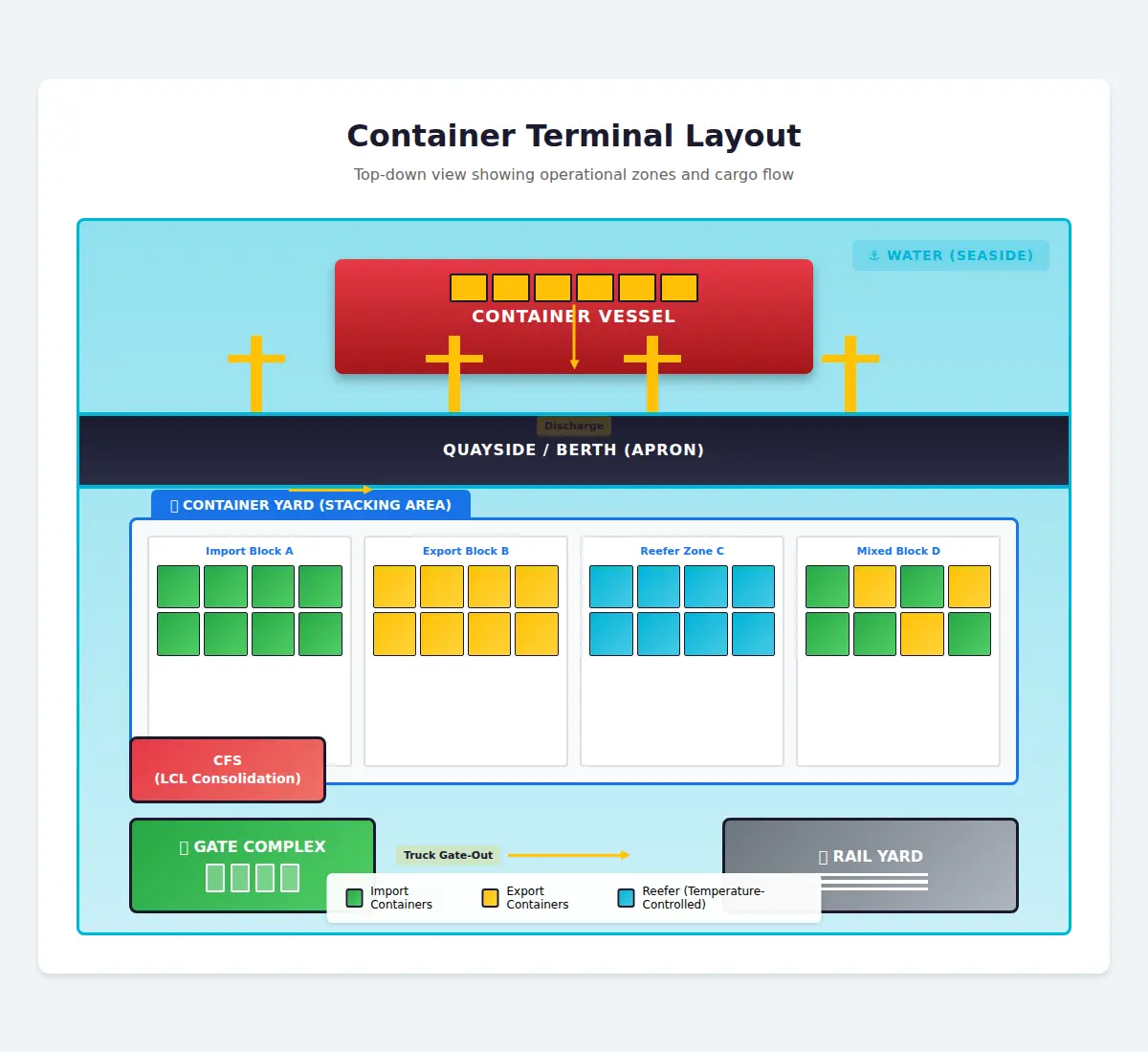

Container Terminal Layout

A modern container terminal is organized into distinct operational zones, each designed for a specific stage of the container handling process:

- Gate complex — The entry and exit point for trucks. Equipped with radiation portals, OCR cameras for automatic container number recognition, and weigh-in-motion scales.

- Container yard — The storage area where containers are stacked, typically 4–5 containers high for dry cargo. Organized into blocks, rows, bays, and tiers. Reefer containers are placed in dedicated areas with electrical plug points.

- Quayside (berth) — The waterside edge where vessels dock. Ship-to-shore (STS) quay cranes operate here, lifting containers between vessel and shore.

- Intermodal rail yard — Many large terminals connect directly to rail networks, enabling containers to transfer between ship and train without leaving the terminal.

- Container freight station (CFS) — A warehouse area for LCL cargo consolidation and deconsolidation.

Vessel Berthing and Berth Allocation

When a vessel approaches port, the terminal operator must assign it a berth — a specific docking position along the quay wall. Berth allocation is one of the most complex planning problems in terminal operations because it must account for:

- Vessel dimensions — Length, beam, and draft determine which berths are physically suitable.

- Crane availability — Larger vessels require 4–6 simultaneous quay cranes; the allocated berth must have enough crane coverage.

- Tidal windows — Deep-draft vessels (such as Ultra Large Container Vessels with 16+ meter drafts) may only be able to enter or leave during high tide.

- Container volume — The number of moves (lifts) determines how long the vessel will occupy the berth.

- Schedule priority — Alliance partners and long-term customers may receive preferential berthing windows.

A typical Ultra Large Container Vessel (ULCV) carrying 20,000+ TEU may require 36–48 hours at berth, with 5–6 quay cranes working simultaneously to achieve 150–200 crane moves per hour across the vessel.

Terminal operators plan berth allocation 1–2 weeks in advance using vessel schedule data, but continuously adjust as vessels arrive early or late. A delay of just a few hours on one vessel can cascade across the entire berth schedule.

Quay Crane Operations and Vessel Loading

Ship-to-shore (STS) quay cranes are the defining equipment of a container terminal. These massive gantry cranes straddle the quay edge and reach across the vessel's beam to lift containers on and off the ship.

Key operational concepts:

- Crane productivity is measured in moves per hour (MPH). A modern crane achieves 25–35 moves per hour. Terminal productivity is measured across all cranes working a vessel simultaneously.

- Twin-lift and tandem-lift operations handle two 20-foot containers at once, significantly increasing throughput.

- Bay plan / stowage plan — Before any loading begins, the carrier's planner creates a detailed stowage plan specifying exactly where each container will be placed in the vessel's cell structure. Factors include container weight (heavy on bottom), destination port (discharge sequence), dangerous goods segregation, and reefer plug positions.

- Hatch covers — Below-deck containers require removing and replacing hatch covers, adding time to the operation. Containers loaded above deck ("on deck") are faster to handle but more exposed to weather.

Container Yard Management

The container yard is the terminal's storage buffer between vessel and landside operations. Yard management is the art of placing containers in positions that minimize unnecessary moves (called reshuffles or rehandles) when retrieving them later.

Yard equipment types

| Equipment | Description | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Rubber-Tired Gantry (RTG) | Mobile gantry crane on rubber tires, spans 6–8 rows wide, stacks 5–6 high | Most common worldwide |

| Rail-Mounted Gantry (RMG) | Fixed gantry crane on rail tracks, fully automatable | Automated terminals (e.g., Rotterdam, Long Beach) |

| Reach Stacker | Mobile machine with telescopic arm, handles 1 container at a time | Smaller terminals, rail yards, empty depots |

| Straddle Carrier | Self-propelled vehicle that lifts containers between its legs | Common in Australian and some European terminals |

Stacking strategies

Efficient yard planning groups containers by:

- Vessel and port of discharge — Export containers destined for the same vessel are stacked together.

- Weight class — Heavier containers placed lower to reduce rehandles during loading.

- Container type — Reefers, dangerous goods, out-of-gauge cargo, and empties each go to dedicated zones.

- Dwell time — Import containers expected to be picked up soon are placed in more accessible positions.

Rehandles — moving containers on top of others to access the one underneath — are a major source of inefficiency. Each rehandle adds time and cost. Well-managed terminals keep their rehandle ratio below 1.5 moves per container pickup.

Gate-In and Gate-Out Procedures

The gate is where containers transition between the terminal and the external trucking network. Modern terminals process hundreds of truck transactions per hour through automated gate systems.

Gate-In (Delivering a Container to Terminal)

- Truck arrives at the terminal gate with a booking reference or pickup order.

- Identification — OCR cameras automatically read the container number, truck license plate, and chassis number. Radiation portal monitors scan for anomalies.

- Documentation check — The Terminal Operating System (TOS) validates the container against the booking. For exports, the system checks that the booking is confirmed and the cargo cut-off time has not passed.

- Seal verification — The container seal number is recorded and compared against shipping documents.

- Container inspection — Gate clerks or cameras check for visible damage. Any damage is photographed and recorded as an Equipment Interchange Receipt (EIR).

- Yard assignment — The TOS assigns a yard position, and the truck is directed to the designated block for unloading.

Gate-Out (Picking Up a Container from Terminal)

- Release verification — The TOS checks that customs clearance is complete, all holds are released (carrier hold, customs hold, terminal hold), and any applicable charges are paid.

- Truck identification — The trucker's pickup reference is validated against the release order.

- Container retrieval — The yard crane retrieves the container from its stack position and loads it onto the truck.

- EIR issuance — An Equipment Interchange Receipt is generated documenting the container's condition at departure.

Cargo cut-off and documentation cut-off are critical terminal deadlines. Cargo cut-off (typically 24–48 hours before vessel departure) is the last moment a container can gate-in for a specific vessel. Documentation cut-off (typically 12–24 hours before departure) is the deadline for submitting shipping instructions.

Terminal Operating Systems (TOS)

A Terminal Operating System is the software platform that coordinates all terminal activities. The TOS is to a container terminal what an air traffic control system is to an airport — it orchestrates the movement of every container, piece of equipment, and truck in real time.

Key TOS functions include:

- Berth planning — Scheduling vessel arrivals, crane assignments, and labor shifts

- Yard planning — Assigning container positions to optimize space utilization and minimize rehandles

- Gate management — Automating truck processing, appointment systems, and documentation validation

- Equipment dispatch — Directing cranes, yard trucks, and straddle carriers to their next task

- EDI/API integration — Exchanging data with shipping lines, customs systems, trucking platforms, and freight forwarders

Major TOS platforms used globally include Navis N4, TBA OSCAR, Cosmos (by Ports America), and TOPS by RBS.

Free Time and Storage Charges

Terminals grant a period of free time during which containers can remain in the yard without incurring charges. After free time expires, port storage charges (also called ground rent) begin to accrue.

| Charge Type | Applied By | Where | Typical Free Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Port storage / ground rent | Terminal operator | At the terminal yard | 3–7 days for imports; 5–7 days for exports |

| Demurrage | Shipping line | At the terminal (before gate-out) | 4–7 days, varies by carrier and trade lane |

| Detention | Shipping line | Outside the terminal (at consignee) | 4–7 days after gate-out |

Port storage charges are separate from carrier demurrage charges, but they can overlap. A container sitting at terminal beyond free time may incur both terminal storage fees (paid to the terminal operator) and demurrage (paid to the shipping line) simultaneously.

Resources

| Resource | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Port Economics, Management and Policy | Comprehensive open-access textbook on port operations and terminal design | porteconomicsmanagement.org |

| World Port Source | Database of global ports with maps, statistics, and operational details | worldportsource.com |

| AAPA (American Association of Port Authorities) | Industry association with port statistics and policy resources | aapa-ports.org |

| MarineTraffic | Live vessel tracking and port arrival/departure schedules | marinetraffic.com |

| FMC (Federal Maritime Commission) | U.S. regulator overseeing ocean shipping, including terminal practices | fmc.gov |

Related Topics

- Container Types — the equipment that flows through container terminals

- Demurrage & Detention — charges that accrue when containers overstay at terminals

- Bill of Lading — the key document that must be surrendered before cargo release

- Drayage — trucking operations that connect terminals to inland destinations