Air Waybill (AWB)

The Air Waybill (AWB) is the principal transport document in air freight. It serves as a contract of carriage between the shipper and the airline, a receipt for goods tendered for transport, and a document that accompanies cargo through every stage of its journey — from origin airport to final destination. Unlike the ocean Bill of Lading, an AWB is non-negotiable and does not confer title to the goods.

Understanding the AWB is fundamental for anyone involved in air cargo operations, as it governs the legal relationship between the parties, facilitates customs clearance, and enables shipment tracking across the global air freight network.

What is an Air Waybill

An Air Waybill is a standardized document governed by international aviation conventions and IATA (International Air Transport Association) regulations. It performs three core functions:

-

Contract of carriage — The AWB constitutes evidence of the agreement between the shipper and the carrier for the transportation of goods by air. It incorporates the carrier's conditions of carriage, including liability limitations.

-

Receipt for goods — When the carrier accepts cargo, the AWB serves as proof that the goods have been received in apparent good order and condition (unless otherwise noted).

-

Customs and regulatory document — The AWB provides the information that customs authorities and regulatory agencies need to process cargo at both origin and destination, including a description of goods, declared value, and routing details.

Legal Framework

The legal basis for air waybills rests on two key international conventions:

-

The Warsaw Convention (1929) — The original international treaty governing air carrier liability and documentation requirements. It required a paper air waybill for all international air cargo shipments and established carrier liability limits.

-

The Montreal Convention (1999) — The modern successor that updated and unified the Warsaw system. Crucially, the Montreal Convention permits the use of electronic records in place of paper air waybills (Article 4), paving the way for the e-AWB. It also modernized liability provisions, establishing carrier liability at 22 Special Drawing Rights (SDR) per kilogram for cargo damage or loss (approximately $30 USD/kg).

Unlike an ocean Bill of Lading, the Air Waybill is always non-negotiable. It cannot be endorsed or transferred to a third party to claim ownership of the goods. Cargo is released to the named consignee upon proper identification — no surrender of the original document is required.

Master AWB vs House AWB

In the air freight industry, two types of air waybills operate in a hierarchical relationship:

Master Air Waybill (MAWB)

The Master Air Waybill is the contract of carriage between the airline (carrier) and the freight forwarder or consolidator. It covers the entire consolidated shipment as a single unit from the airline's perspective. The MAWB is issued by the airline or its appointed ground handling agent and carries the airline's three-digit IATA prefix in its numbering.

Key characteristics:

- Issued by the actual carrier (airline)

- The shipper field shows the freight forwarder (not the actual goods owner)

- The consignee field shows the destination agent (the forwarder's partner at destination)

- Covers the entire consolidation as one shipment

House Air Waybill (HAWB)

The House Air Waybill is the contract of carriage between the freight forwarder and the individual shipper. When a forwarder consolidates multiple shipments from different shippers into a single airline consignment, each shipper receives their own HAWB while the forwarder holds the MAWB.

Key characteristics:

- Issued by the freight forwarder

- The shipper field shows the actual goods owner

- The consignee field shows the actual receiver of the goods

- Multiple HAWBs map to a single MAWB in a consolidation

For direct shipments — where a single shipper books space directly with the airline or sends a shipment large enough to fill an entire ULD — only a MAWB is issued. The shipper and consignee on the MAWB are the actual parties, and no HAWB is needed.

Key Information on an AWB

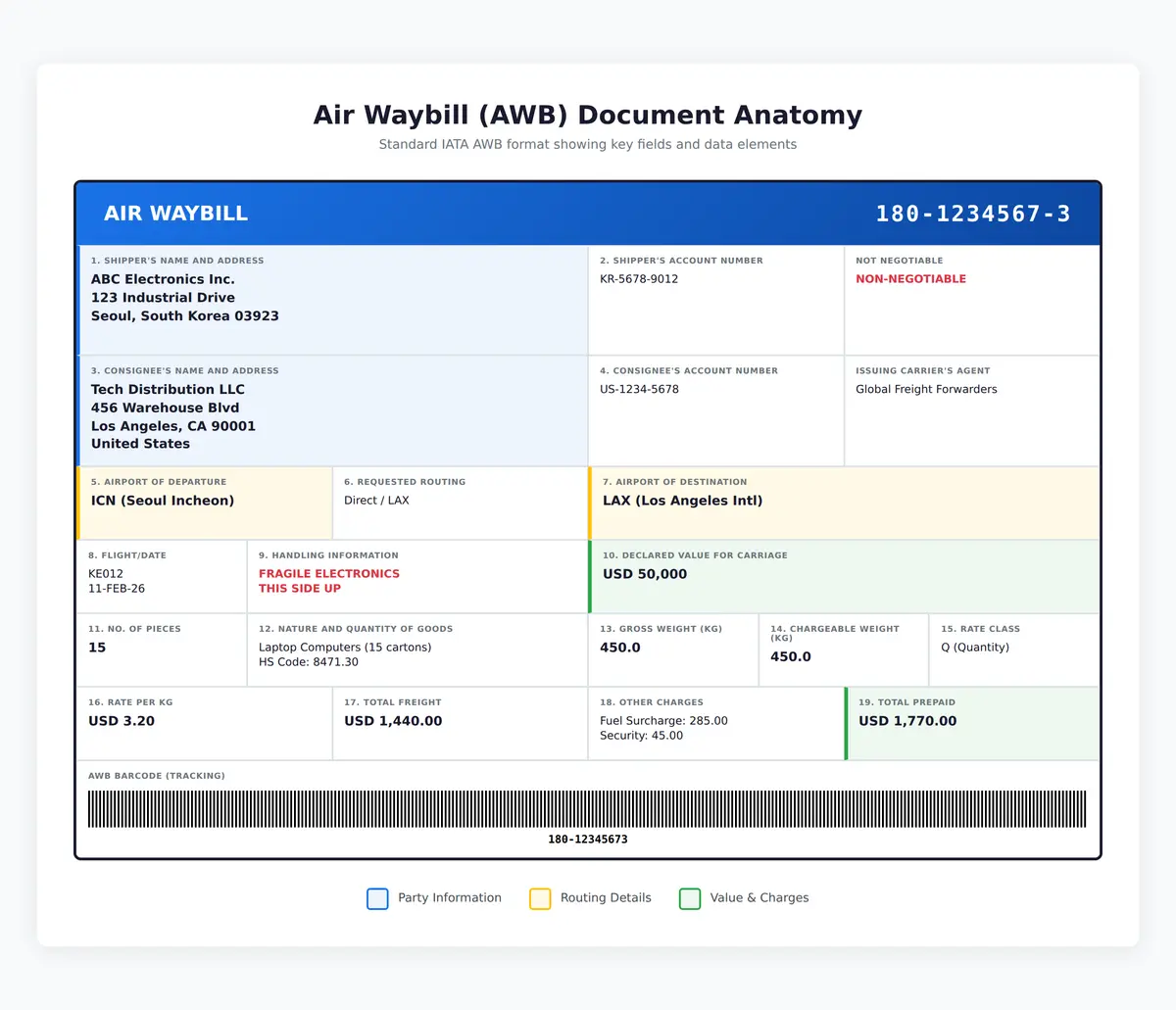

A standard Air Waybill contains detailed information organized into standardized boxes. The layout follows IATA Resolution 600a, ensuring global consistency regardless of the issuing carrier. The following diagram shows a typical AWB document with all major fields:

AWB Field Descriptions

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| AWB Number | Unique 11-digit identifier (airline prefix + serial number) |

| Shipper (Name & Address) | Party tendering the goods for transport |

| Consignee (Name & Address) | Party to whom the goods are destined |

| Issuing Carrier's Agent | Freight forwarder or agent completing the AWB |

| Airport of Departure | Origin airport (IATA 3-letter code) |

| Airport of Destination | Final destination airport |

| Routing (By First/Second/Third Carrier) | Transit points and connecting carriers |

| Flight/Date | Specific flight number and date of departure |

| Nature and Quantity of Goods | Description, number of pieces, commodity code |

| Gross Weight | Total weight including packaging |

| Dimensions | Length × Width × Height per piece |

| Rate Class | Tariff classification (M = minimum, N = normal, Q = quantity, C = specific commodity) |

| Chargeable Weight | Greater of actual weight or dimensional weight |

| Rate/Charge | Rate per kilogram and total freight charge |

| Declared Value for Carriage | Value declared by shipper for liability purposes (or NVD — No Value Declared) |

| Declared Value for Customs | Value for customs duty calculation |

| Handling Information | Special instructions (e.g., perishable, live animals, dangerous goods) |

AWB Numbering System

Every Air Waybill carries a unique 11-digit number that follows the IATA-standardized format. This number is the primary identifier used for tracking, billing, and document retrieval throughout the cargo journey.

Structure of an AWB Number

┌───────────┬────────────────────────┬───────────┐

│ Prefix │ Serial Number │ Check │

│ (3 digits)│ (7 digits) │ Digit │

├───────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────┤

│ 180 │ 1234567 │ 3 │

│ (Korean │ (Unique sequential │ (Modulus 7│

│ Air) │ number) │ of serial│

│ │ │ number) │

└───────────┴────────────────────────┴───────────┘

Full AWB number: 180-12345673

Airline prefix (3 digits): Identifies the issuing carrier. Each IATA member airline has a unique numeric prefix. For example:

- 176 — Emirates

- 180 — Korean Air

- 074 — KLM

- 057 — Air France

- 020 — Lufthansa

- 235 — Turkish Airlines

Serial number (7 digits): A unique sequential number assigned by the airline from its allocated stock of AWB numbers.

Check digit (1 digit): The last digit is calculated as the remainder when the first 7 digits of the serial number are divided by 7 (modulus 7). This allows systems to detect data entry errors instantly. For example, if the serial number is 1234567: 1234567 ÷ 7 = 176366 remainder 5, so the check digit would be 5.

Always verify the check digit when entering AWB numbers manually. An incorrect check digit is the fastest indicator of a keying error and will cause tracking and customs failures.

Electronic Air Waybill (e-AWB)

The e-AWB is the electronic equivalent of a paper air waybill. Rather than exchanging physical documents between forwarders, airlines, and ground handlers, the shipment data is transmitted electronically through cargo messaging systems while a digital record replaces the paper original.

Why e-AWB Matters

The traditional paper AWB process required multiple copies (up to 12 copies in a standard set) to be printed, signed, and physically transported alongside the cargo. This created delays, errors from manual transcription, and significant handling costs.

The e-AWB eliminates paper by transmitting shipment data via Cargo-IMP or Cargo-XML messages (IATA standard messaging formats) between the forwarder's system and the airline's cargo management system.

IATA Resolution 672 — The Multilateral e-AWB Agreement (MeA)

IATA's Multilateral e-AWB Agreement is the legal framework that enables e-AWB. Rather than requiring bilateral agreements between every forwarder and every airline, the MeA creates a single multilateral structure:

- Airlines and forwarders each sign the MeA once

- This automatically establishes e-AWB capability with all other signatories

- The MeA designates the electronic record as the legal contract of carriage

- Over 200 airlines and thousands of freight forwarders have signed the MeA

e-AWB Adoption

The e-AWB penetration rate has grown steadily. IATA has been driving adoption across all markets, with the goal of achieving 100% e-AWB across feasible trade lanes. As of recent years, global e-AWB penetration has exceeded 80% on eligible trade lanes. Some regions — particularly where regulatory requirements still mandate paper customs documentation — have lagged behind, but initiatives like Brazil's 2024–2025 trial program demonstrate continued expansion.

Key Message Types in e-AWB Processing

| Message Code | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| FWB | Freight Waybill | Transmits the full AWB data electronically |

| FHL | Freight House List | Lists all HAWBs under a MAWB (consolidation manifest) |

| FMA | Flight Manifest Acknowledgment | Airline confirms booking |

| FSU | Freight Status Update | Status milestones: RCS (received), DEP (departed), ARR (arrived), NFD (notified) |

| FFM | Flight Manifest | Cargo manifest for a specific flight |

Common Mistakes and Best Practices

Understanding common AWB errors helps prevent costly delays:

-

Incorrect shipper/consignee details — Mismatched names or addresses cause customs holds. Always verify against purchase orders and letters of credit.

-

Wrong commodity descriptions — Vague descriptions like "general cargo" trigger inspections. Use accurate, specific descriptions aligned with customs tariff codes.

-

Weight discrepancies — Differences between declared and actual weight lead to billing disputes and potential safety issues (aircraft weight and balance). Always weigh cargo accurately.

-

Missing handling codes — Dangerous goods, perishables, and valuable cargo require specific handling codes (e.g., DGR, PER, VAL). Omitting them can result in rejection at acceptance.

-

Forgetting the HAWB–MAWB linkage — Ensure every HAWB is properly manifested under its MAWB. Orphaned HAWBs cause delivery failures at destination.

Most freight forwarders use Transport Management Systems (TMS) that auto-populate AWB data from booking records, reducing manual errors. Integration between forwarder and airline systems via Cargo-XML further minimizes discrepancies.

Resources

| Resource | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| IATA e-AWB Program | Official IATA page on e-AWB adoption, MeA agreement, and implementation guides | iata.org/e-freight |

| Montreal Convention (Full Text) | The international convention governing air carrier liability and AWB requirements | iata.org/mc99 |

| IATA Cargo-XML Standards | Technical messaging standards for electronic cargo data exchange | iata.org/cargo-xml |

| IATA CASS (Cargo Accounts Settlement System) | How air freight charges and AWB-based billing are processed between agents and airlines | iata.org/cass |

| ICAO Doc 9626 | ICAO manual on air cargo facilitation and documentation standards | icao.int |

Related Topics

- ULD Types — The containers and pallets that cargo referenced on an AWB is loaded into

- Dimensional Weight — How chargeable weight on the AWB is determined

- Dangerous Goods — Special AWB handling requirements for hazardous materials

- Bill of Lading — The ocean freight equivalent, with key differences in negotiability

- Documentation Flow — How the AWB fits into the broader freight forwarding document lifecycle